Databending Part 1—Raw Data in Audacity

All posts in this series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5

Let's start today off with some sounds right out of the gate:

What you're listening to is a segment of the recently departed Finale notation program being treated as an audio file. Notice how the tone and envelope almost sound like a drum machine. The rhythm is in a wonderful place between random and regular—there are sequences of sounds that almost repeat, and that almost sound like a kick-snare dance beat, but it's not quite regular enough to dance to. It reminds me of the rhythmic qualities of some of Autechre's music (see e.g., Tapr at around 1 minute, or VI Scose Poise).

This process of treating non-audio data as if it's an audio file (along with other such artistic data reinterpretations) is often called “databending.” Today I'll talk about how this reinterpretation works for audio, how to do it using simple tools such as Audacity, and what kinds of files tend to produce different kinds of sounds. In further post(s), I will dive deeper into analyzing music and art that uses this and similar techniques—both my and others' work.

How It Works

First, sound is compressions and rarefactions (i.e., the opposite of compression) in the air or another substance (see an animation here). These increases and decreases in pressure can be represented as a rising and falling line. In a digital audio file, we take repeated readings or “samples” of this rising and falling pressure at very rapid intervals in time (the “sample rate”), and represent the height of the rising and falling line at each reading using an integer value.

Since any computer file is just a list of numbers—binary values stored on the computer's drive—we can take the list of numbers from any file and treat them as a list of amplitudes in an audio file. For significant portions of many files, the resulting audio mostly sounds like white noise, but most files have at least some stretches in which percussive rhythms and glitchy, buzzing pitches appear.

How to Do It

In Audacity, go to File > Import > Raw Data, choose any file and import it. The “Raw Data” import instructs Audacity to ignore the encoding of the original file (executable, document, image, library, etc.) and allows any file to be treated as audio. There are a number of settings in the “Import” menu, but this is enough to get started. I usually use signed 16-bit PCM, default endianness, one channel, and 44100 Hz for the sample rate. I chose 16 bits and 44100 Hz because those are the values in CD-quality audio, one channel so all the data is laid out linearly in a single sound, and default endianness because it seems to often produce the clearest results.

What Kinds of Files?

Since I primarily use macOS and some Linux, this discussion will be most specific to those OSes, but similar things work well on Windows. The files I find work best are binary files. While all computer files use binary code in some form, “binary file” usually refers to a file that does not encode text.

The two categories of binary files I usually end up using most are program files (e.g., Unix executable files/Windows .exe files) and libraries (.dylib, .dll, .a, .so files, etc.). You can think of libraries as “subunits” in a program—a library might handle encoding mp3 files, connecting to the internet, or another small task that many different programs need. The program files I describe above might combine a number of libraries along with unique code for that program, and you can often run a full program by double-clicking on them. I've found both categories to produce interesting sounds, and we will return to some differences between databending program files and libraries.

For now, let's compare a snippet of a PDF and one from a binary shared library file. This is an excerpt of the audio generated from a PDF. [1] Other than white noise, the entire file sounds almost exactly like this. Note the rapid “tremolo” effect. My best guess is that this is because text is fairly repetitive from a data perspective—a few characters grouped into short words, separated by spaces and paragraph breaks. Rapid repetition of short blocks of similar data sounds like a rhythmic tremolo:

It's certainly an interesting enough sound, but since the entire file sounds essentially the same, I don't find it as productive to look at text files, PDFs, etc.

This next recording is an excerpt of the file libicudata.73.dylib found in the Calibre E-book manager on macOS. A macOS application (.app) is technically a folder, and Audacity will refuse to import folders as raw data. To get to this binary file, right-click, “Show Package Contents,” and look in Contents > Frameworks. [2] There are usually a number of folders in macOS applications, and any binary file can potentially be interesting. I usually look for ones that are at least a few megabytes in size—since a good portion of most files is white noise, the “interesting” parts of smaller files are rarely as long and varied as I would like:

I want to draw your ears to the rhythmic character of this sound. The PDF had two elements—a low motor-like buzz, and a burst of white noise—and rapidly “toggles” between them. In contrast, this library file has high “wheedling” tones; medium-register “beeps” that poke out through the texture; chugging, clicking noises that remind me of a receipt printer; low tones that rapidly bend up and down; sustained, buzzing bass notes; and many other small nuances.

I particularly like the character of the transients and spectral flux in these sounds. Transients are rapid, momentary changes in a sound, such as percussive “attacks” at the start of notes. “Spectral flux” refers to how rapidly the spectral density of the sound changes—how rapidly areas of greater or lesser energy change and move up and down the spectrum.

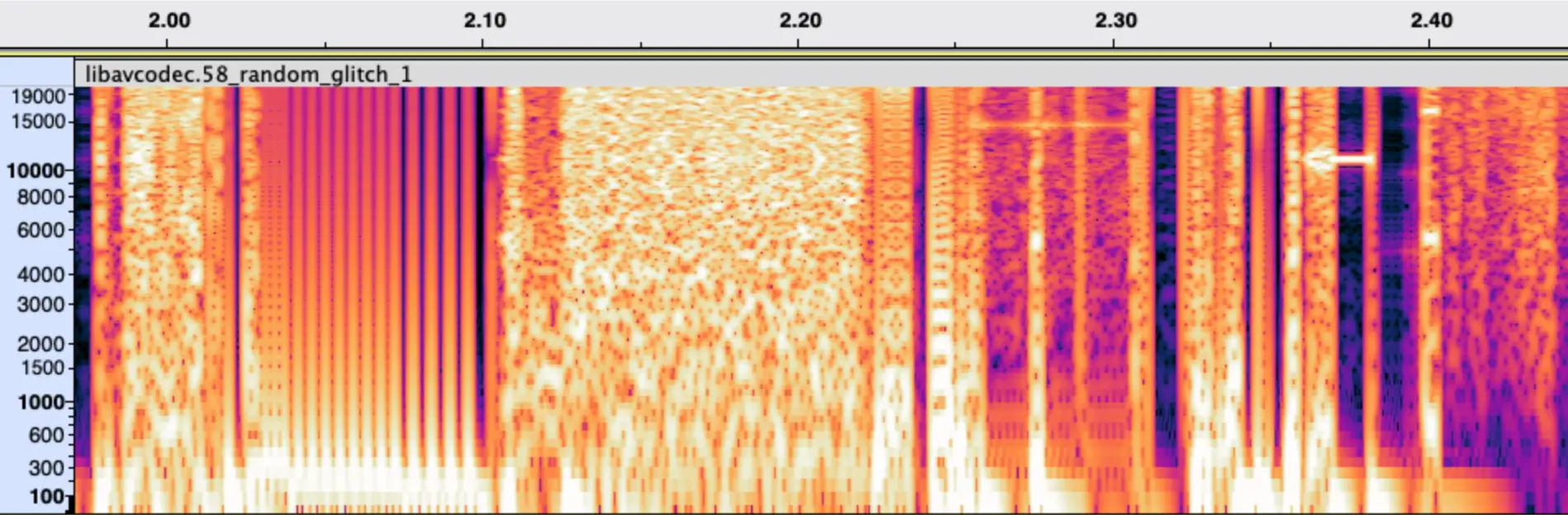

Have a listen for these two features in this sound from the libavcodec audio codec library:

Notice the rapid, sharp discontinuities, both in time and in frequency. Extremely short bursts of static have sharp attacks and releases. Piercing tones—often in a register so high it doesn't even feel like a note, just a needling noise—rapidly appear and disappear, varying significantly in pitch each time. Because these tones are so high, and because they are constantly interrupted with noise and vary in pitch so much, the string of tones sounds like noise, rather than any melody.

These are the kinds of sounds I tend to seek out for composing: rhythmically interesting, containing a mix of pitched and percussive elements, and with detailed, complex transients and frequency content.

Similarity and Scarcity

Now that you've listened to libicudata.73.dylib as audio, try comparing it to the excerpt of the Finale binary file at the start of today's article. The two files contain some of the same sounds!

This creates a challenge in finding new sounds. Similar to my experience composing with radio transmissions (as I describe in the “challenges” section of this post), once you listen to the “sonified” data from enough files, commonalities start to become apparent. Many programs use some of the same .dylib files, and I imagine Finale either contains this exact file or some of the component code this file uses. [3] Even differently-named library files sometimes contain similar elements—likely re-used code patterns, or further library code compiled in.

The process of finding these sounds is also fairly slow and painstaking. [4] After importing and cleaning up the files, there is a huge amount of material to get through, and since the way I divide up the source material is relevant to the composition process, it takes a good deal of back and forth between the long audio files and the composition I'm currently writing before I settle on exactly where my samples should start and end.

Finding Variety

One thing I've found to help a bit is to databend libraries (e.g., .dylib, .dll, .a, .so files), not full program binaries. Since program binaries often incorporate library data (and are thus likely to share sounds with other programs that incorporate the same libraries), it's easier to find variety by looking for different libraries. I can look at the file names instead of being surprised and disappointed when a program file turns out to sound the same as parts of the last one.

In addition to files on macOS, I've tried files from Linux and Windows computers. The Linux files (usually executable files, or libraries such as .a or .so files) tend to sound fairly similar to the macOS ones, but I have had some luck finding variety on Windows. [5] I haven't noticed a clear “macOS sound” or “Windows sound,” but changing OSes does seem to help avoid the issue of programs containing the exact same code.

Even with these approaches, if I want to avoid repeating myself between compositions, at a certain point I need to come up with new ways of using these databending sounds. If I want to retain the interesting character of the sounds, I find that slicing the sample into segments and re-ordering them (rather than e.g., using audio effects, changing playback speed, etc.) is the least “invasive” way of creating variety. Some options include using granular synthesis to make a databending sounds into a glitchy, noisy texture, or chopping up segments of the file and re-sequencing them in a sampler. However, I'm often reluctant to do this, since as previously mentioned, the rhythmic character of the sounds is an important aspect of their charm. How much of this to do is something I'm still experimenting with.

Something interesting to check out is James Bradbury's FluCoMa plenary talk titled “Finding Things in Stuff,” in which he uses Python and the FluCoMa (“Fluid Corpus Manipulation”) toolkit for Max/MSP, SuperCollider, and Pure Data to find the “interesting” sections of databending sessions. I haven't tried his methods yet, but they look promising for at least speeding up the search.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

This past Friday (Jan. 3) marks one year since I was inspired by a Sophie Koonin talk to start writing on this blog! Since then I coded my own comment system, with a similar system to add post likes; added webmentions; and set my site up with Eleventy so that it's extremely easy to post. It makes me happy that I've been able to (mostly) keep up the habit of writing on here, and I'm enjoying writing on here quite a bit.

I'm planning to write a part 2 to today's post that goes into more depth analyzing and discussing works that use databending. There are a number of composers I like who do this, and I think it'll be interesting to collect my responses to their music in one place. I hope to see you then!

This is from a copy of Digital Folklore (2009) by Manuel Buerger, Dragan Espenschied, and Olia Lialina. ↩︎

Note that you will need to right-click, “Show Package Contents,” and copy/paste any files of interest into a new folder before going to the Audacity “Import” menu. It does not seem to be possible to right-click and “Show Package Contents” from the import dialogue in Audacity. ↩︎

The second seems more likely to me, given that a number of other .dylib files or program binary files contain the same or similar sounds, and are often smaller than the ~64.7MB of libicudata.73.dylib. ↩︎

When I import the files, there is a good deal of DC offset and sub-20 Hz noise, and the file is usually at max amplitude. I filter out the frequencies below 20 Hz on each file. This is both useful to remove “mud” and to make it easier to visually distinguish between parts of the audio—what was originally a flat peak amplitude becomes more varied when removing DC offset/infrasound. To make room for the new variation in amplitude, I also have to lower the amplitude prior to filtering. ↩︎

I usually have the best luck with .exe files (executables) or .dll files (libraries) on Windows. Try looking in the subfolders in C:\Program Files or C:\Program Files (x86). ↩︎

---END OF TRANSMISSION---

Leave a Comment