Hypertext, the Memex, and Collaboration as Socialization

A few days ago I was part of a Facebook thread about music notation. Composer Christopher Cerrone posted asking what way of notating a complex rhythm would be most readable. The general consensus was something akin to what Thomas Adés does in e.g., “Lieux Retrouves,” movement 2 in the piano part: notate it two different ways, with one shown above the other to clarify how the instruments align.

Within the thread, there were a number of interesting finer points raised, but as I watched the discussion continue, I was a bit sad to think that it would all disappear in the stream of future posts, and that even if the discussion were somehow pinned, it would not be easily accessible from a search engine.

I have seen a number of people express similar sentiments in the free and open-source software world. Services like Discord are popular (and admittedly easy) ways to discuss the development process. However, there are two big issues: 1) the discussion is not easily searchable from the rest of the Internet, and 2) the linear nature of a chat means that the same questions are raised again and again.

We could be much more daring

The problem of platforms that are not searchable on the “clearnet” (e.g., Discord) is better on platforms such as the Fediverse, but even there, posts still appear in a linear format, and the platform design doesn't make it easy to create a complex, interlinked, lasting database of knowledge that is easy to return to or discover.

It didn't previously occur to me that a linear “feed” of posts was something to worry about—it is, after all, how blogs, social media…essentially all of the Internet on which I socialize works. I recently read “It's easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of Instagram.” The author had previously proposed “ethical anti-design”—design patterns that make it harder to be “sucked into” scrolling through Internet-published media. This new article comments that

If you're trying to make a truly “post-Facebook” social media platform and you start with “it's like Instagram, but for the Fediverse,” then you've already lost.

In “against the dark forest,” Erin Kissane similarly writes that “…our failure to remember that it doesn’t have to be this way is a failure not only of imagination, but of nerve.”

What would it look like to interact with other people on the Internet if we were daring and started from first principles? Are there ways to do this that we miss if we try to reform existing models? I don't know, but it's been on my mind, and I want to discuss some of the perspectives on hypertext I've recently read in order to at least start thinking about alternatives to reforming the endlessly-scrolling feed.

Gardens vs Streams

I love hypertext. Lately I've been on a kick of rediscovering how nice and powerful the humble hyperlink is (and thinking about how some parts of the Internet don't give it enough value). I have, for example, started using the note-taking program Obsidian, which makes it easy to hyperlink between notes and to visualize the nets of links in graph form, giving me a new way to look at my personal knowledge store. In another cool use of hypertext, the band Magdalena Bay did a promotional page for a recent album that includes a map of linked pages with art and multimedia, reminding me how compelling the older practice of hypertext fiction and art can be.

An article by misinformation researcher Mike Caulfield, “The Garden and the Stream: A Technopastoral” started me thinking about different approaches to hypertext. Some of those approaches are much more conducive than others to the kinds of communal knowledge-building I mentioned at the start. Caulfield contrasts the “garden” and the “stream.” The stream

replaces topology with serialization. Rather than imagine a timeless world of connection and multiple paths, the Stream presents us with a single, time ordered path with our experience (and only our experience) at the center.

The stream is Twitter and Facebook feeds—as I mentioned, even the Fediverse and blogs on the IndieWeb, both of which I much prefer to socia media silos, share posts in chronological streams. In the music notation discussion above, the discussions and ideas will drift away down the stream, without a straightforward means of building on them, linking between them and others, and preserving them for later return.

In contrast, the garden is

the web as topology. The web as space. It’s the integrative web, the iterative web, the web as an arrangement and rearrangement of things to one another. […]

Every walk through the garden creates new paths, new meanings, and when we add things to the garden we add them in a way that allows many future, unpredicted relationships.

As Caulfield mentions, Vannevar Bush proposed the “memex” hypertext device in his 1945 essay “As We May Think.” The memex would allow a researcher to create links between research documents—a web-like means of accessing information which Bush contrasts with the tree-like library card catalog.

In contrast with the use of hypertext on the modern Web (perhaps excluding wikis), the memex uses links as a means of association, rather than a “web of 'hey this is cool' one-hop links.” The links bring documents and excerpts together to “form a new book,” as Bush puts it, as well as allow a given document or excerpt to form part of multiple “new book[s].” What's more, networks of associations can be named, and can be referred to as objects in their own right. This video demonstration includes excerpts from Bush's essay in the voice over, and at the linked timecode (1:13), mentions the possibility of extracting and sharing a trail of associations with another person, for example.

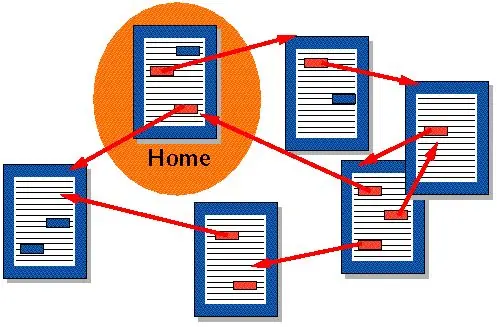

Visualization of the network of links between hypertext documents. Wikimedia Commons

While both the Fediverse and IndieWeb tend to value hyperlinks much more than e.g., Twitter or Facebook (which want to keep users on the platform), links still rarely form shareable associative webs, and are more likely to be used as a means of saying “hey, this is cool.” What would it look like to incorporate at least some of this associative and nonlinear nature (and maybe even the collaborative knowledge-building, and the sharing of knowledge webs) into interactions with people on the Internet?

Why Garden at All?

First of all, you might ask “why?” Vannevar Bush proposed the memex for use by academics. We don't tend to take minutes when in a casual gathering with friends. Why should interactions on the Internet look like editing Wikipedia?

Even in the most radical re-imagining of interaction on the Internet, there is of course still room for status updates, greetings, jokes—for transient, linear posting. However I frequently engage in one form or another of discussion online. Sometimes that looks like the technical musical discussion I began this post with. Sometimes that looks like discussions of the best way to set up a home media center on a Raspberry Pi (a fun project if you're interested!). Sometimes it's discussion of switches for mechanical keyboards, fountain pen preferences, good restaurants in an area, and so on.

After these discussions, I frequently want to save the information to return later. Unless I want to take the time to make a personal copy of this in e.g., Obsidian, I'm left with the built-in bookmarking systems in social media. Facebook and Instagram do have this option, but at best, it's just private folders with no links between things, no ability to comment on connections, and no ability to make a collection public. These are my only current means to save things from drifting away down the stream.

Politically-engaged friends of mine will even write Facebook posts with carefully-researched citations, and I'll often think that I would like to have that knowledge accessible later on. I'll also see people ask “can you make this public?” in the post comments, with the intention of sharing the post, or friends will share screenshots of e.g., a Tumblr thread explaining a social or political issue. The latter is the classic “five giant websites, each filled with screenshots of the other four.” [1]

In short, I think there really is a desire for communal knowledge-building and knowledge-sharing that is not well-served by the parts of the Internet most people use, and we're left with kludges and halfway solutions to try to satisfy this desire. Plus it could be fun! Bonding over creating something with others is something I personally enjoy a lot.

In addition to noticing a potential desire for communal knowledge-building/sharing, I want to see some wild swings, even if they are misses. Would something like this catch on? Who knows! Who cares! The current state of things on the social web is untenable, and we will never know all the results of an approach if we don't try it. Reforming existing models certainly won't tell us all the wild possibilities that could be out there.

Looking Forward

I originally wanted to include some thoughts on writing about/teaching about computer music, and how that relates to collaborative/associative knowledge-building, but this is long enough, and I think I will write about that a bit later. I hope to see you again then!

---END OF TRANSMISSION---

Leave a Comment